2. Sequencing

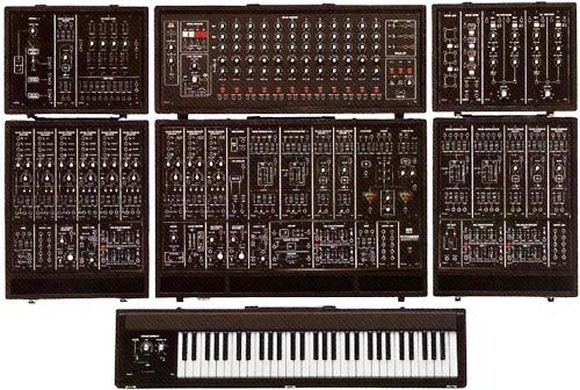

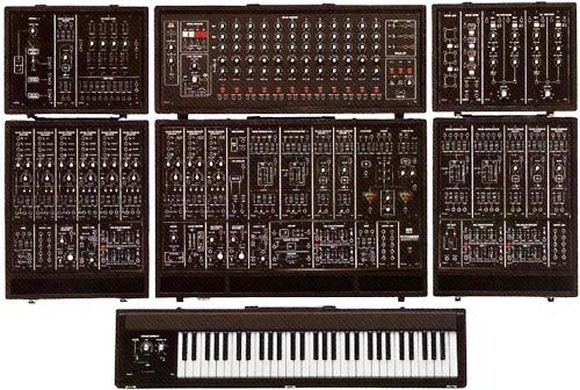

The term sequencing comes from the days of analogue synths. when a cycle of control voltages would be set up to trigger different pitches - more sophisticated models also allowing other properties of the notes such as filter cut-off to be altered. These would be run as a sequence of maybe 8 or 16 notes, and the familiar looped basslines and arpeggios they created can be found in much early 80s synth-based music, although Donna Summers 1977 disco smash I Feel Love is perhaps the most famous early example (produced by Giorgio Moroder). When MIDI and digital instruments arrived on the scene, the concept of sequencing remained - that is to store or record a sequence of notes - but the new technology allowed for far more than just a simple monophonic loop.

Roland System 700

MIDI Musical Instrument Digital Interface. A communications protocol for electronic musical instruments and computers. MIDI can operate over up to 16 independent channels per port and uses 7-bit values (between 0 and 127).

At a basic level MIDI sends information like play this note, this hard, for this long but it can also send many different kinds of control information such as pitch bend, modulation, sustain, filter frequency, fader position, tempo - in fact pretty much anything that you are likely to find on an electronic instrument. So a MIDI sequencer enables you to record not just note and pitch information, but also all your other performance data. Its important to remember that a MIDI sequencer records performance data only - not the actual sound of the performance, as if you make an audio recording. Of course once the data is in the sequencer, you gain the ability to edit the performance and change the sounds being used. You can also tweak various synthesis parameters, quantize notes (automatically correct their timing), and even change the tempo of the music without changing the pitch. When computers arrived in the studio, MIDI data could be displayed on a full-size screen which made composition and all this editing a great deal easier.

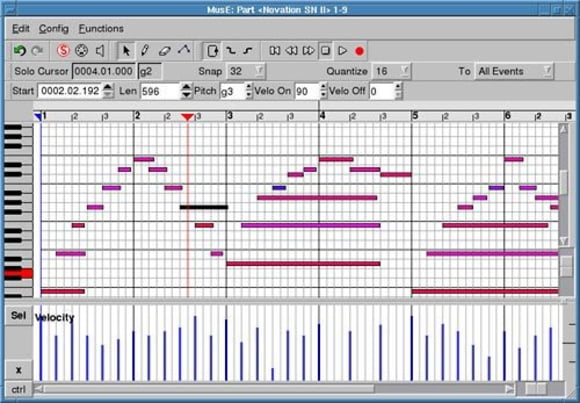

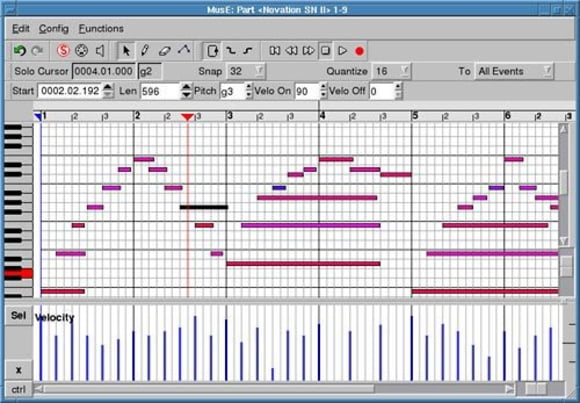

In the early days, there were two major competitors in the software sequencing field, both from Germany - Notator from Emagic (which evolved into Apples Logic) used musical notation to display MIDI data, and Pro 24 from Steinberg (which evolved into Cubase) that opted for what has become the standard MIDI editing interface the piano-roll.

The piano-roll editor is largely unchanged today, and takes its cue from the piano rolls put into player-pianos that you often see in the saloons of Western movies. Its basically a grid with a piano keyboard, and therefore pitch, on the vertical axis, and time, and therefore note duration and position, on the horizontal axis. Piano-roll editors often additionally show controller information such as velocity (how hard a note is played) at the bottom of the screen beneath the notes. Graphic editors of this kind at last allowed people who couldnt read traditional notation to use music software and start composing.

Cubase Piano-Roll

The great advantages presented by MIDI sequencing were not always matched by the usability of the hardware of the day though. As everything went digital in the 90s, many creative musicians sought out discarded analogue hardware and introduced the hypnotic, looping, pulse of analogue sequencing to a new generation of clubbers and ravers. While pop music languished in complex arrangements, the throbbing heart of dance culture worshipped the synth bassline loop. It took a while before software developers came close to replicating that ease of use, but in 1997, Propellerheads released Rebirth RB-338. Rebirth was a virtual model of the Roland TB303 Bassline and TR808 drum machine - suddenly sequencing was intuitive and instant again. In the ten years that followed, Rebirth evolved into the extraordinary Reason software sequencer - probably the best example of combining an analogue-style interface with the depth and programming power of MIDI.

Reason 4