4. Audio interface

In order to connect your computer to the world of audio, you'll need an audio interface. Without a professional audio interface, your computer is of no use for recording. The audio interface is therefore one of the most important components overall in your home studio - in fact, it is so important that we have given it its own online guide. Just look for Audio Interfaces on the online guides page. But we still want to give you a short overview as part of this online guide, too, and tell you what solutions are available, what the specs are of currently available interfaces, and what the most important criteria are when choosing an interface.

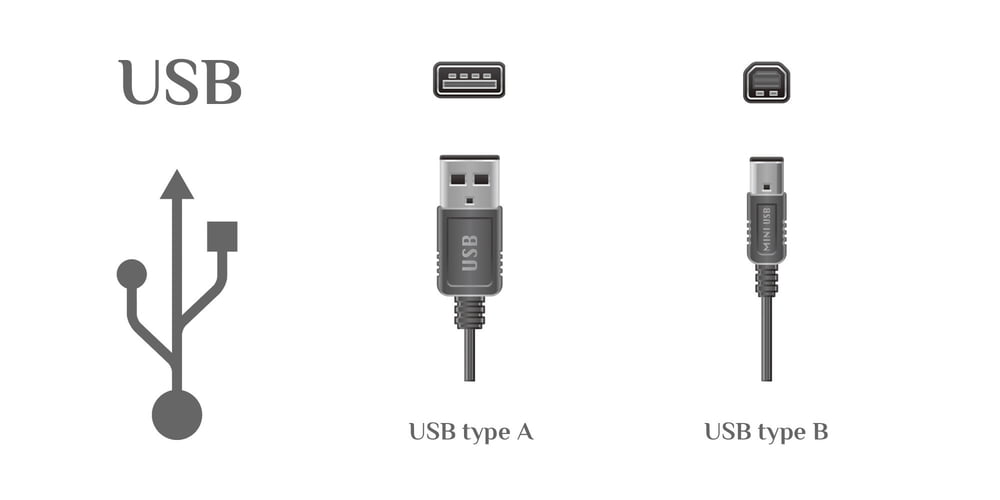

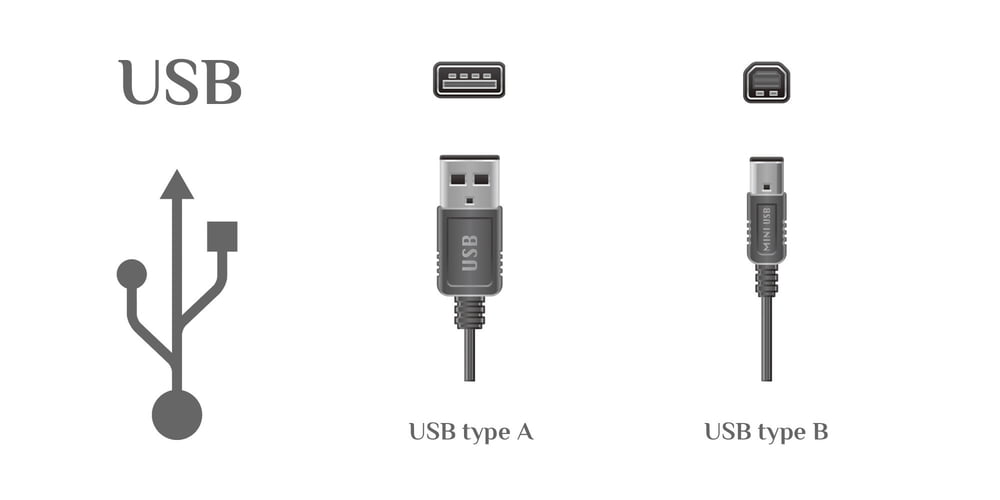

USB 2.0 audio interface

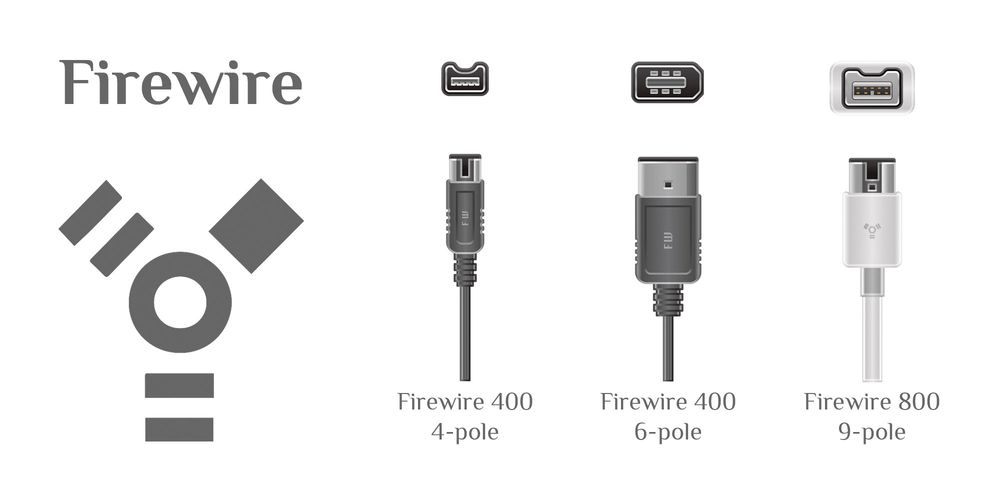

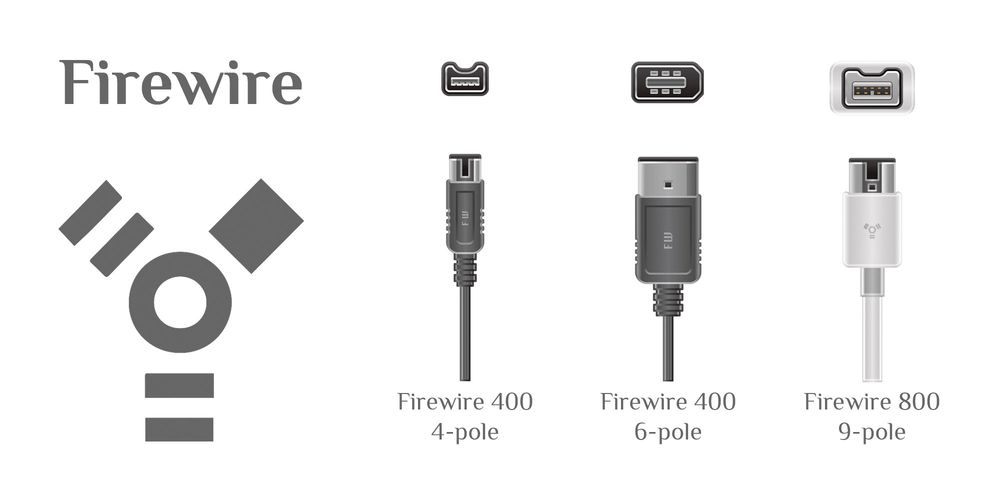

Firewire audio interface

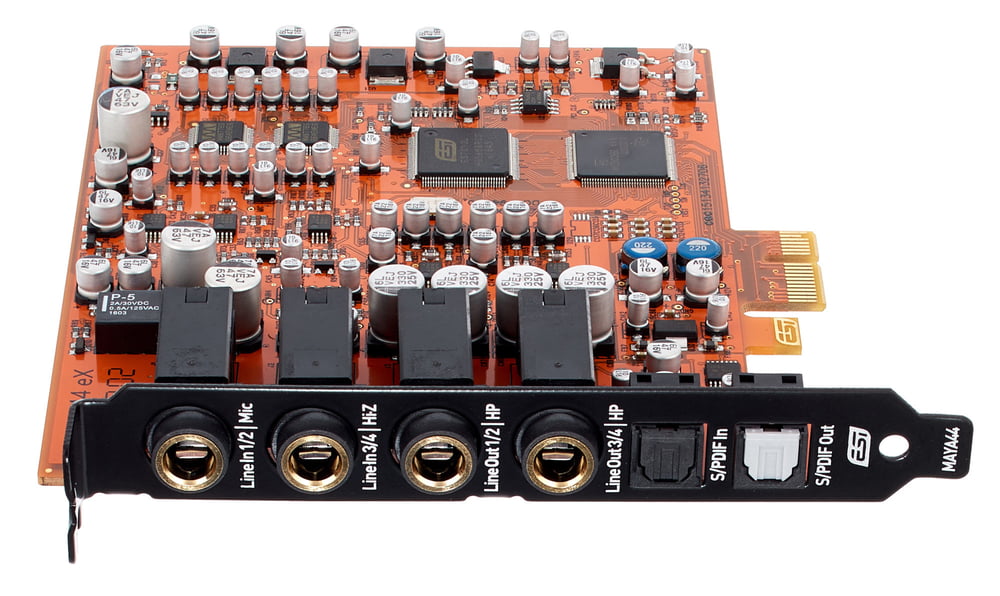

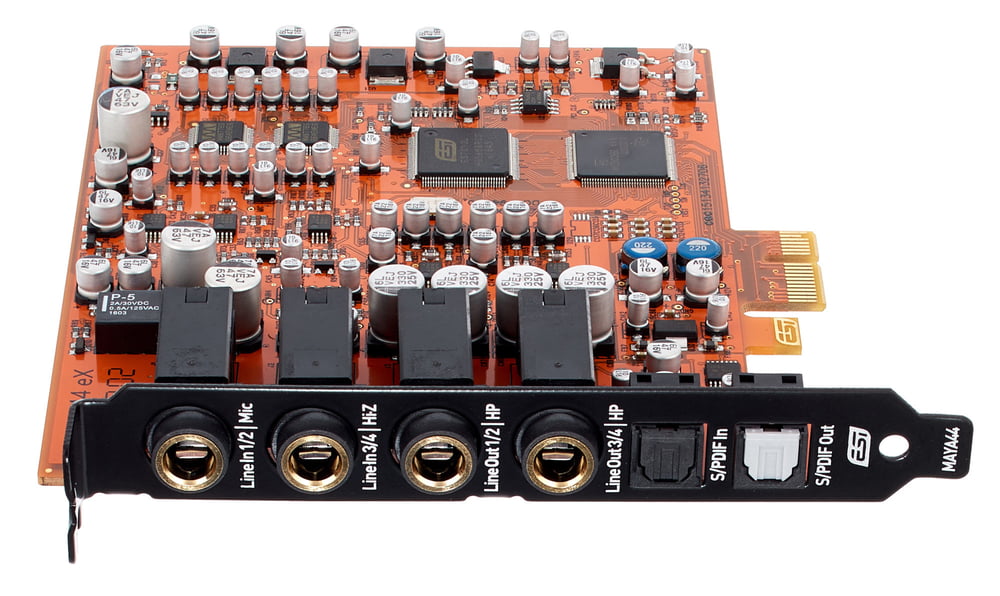

PCIe audio interface

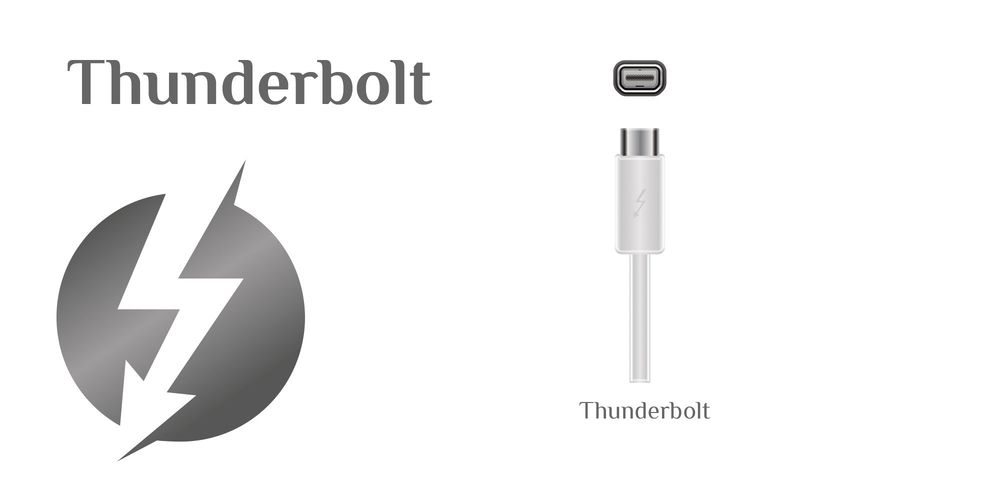

Thunderbolt audio-interface

ASIO / Core Audio

One of the most important features of any audio interface is the driver architecture involved. Onboard and multimedia sound cards are unsuitable for recording, not primarily due to their bad sound quality, which in fact is better than its reputation. The main problem are the system drivers such cards access. Especially Window's proprietary drivers cause significant latencies. For example, if you want to record vocals onto an existing playback, the time between playback and vocals may be skewed by as much as 500 ms. This makes a useful vocal performance impossible.

Audio interfaces therefore do not operate with proprietary Windows drivers, but with ASIO drivers instead (Core audio drivers on Macs). ASIO stands for Audio Stream Input Output and was developed by the Steinberg company. ASIO drivers allow for direct and fast communication between the recording software and the audio interface. This reduces latencies into the low single-digit millisecond range.

Interface formats

Many manufacturers offer PCI/PCIe audio cards for installation in your computer. The fast PCI(e) data bus is generally very well suited for audio applications with low latencies. The audio ins and outs are located either directly on the mounting panel or are brought to the exterior with breakout cables or boxes. If you want to buy a PCI(e) audio card, you need to find out beforehand which bus type your computer features, since PCI and PCIe are not compatible thanks to their different plugs.

Electromagnetic interference may be a problem with PCI(e) cards. The interior of a PC casing is a really hostile environment for audio cards regarding electric and magnetic interference fields as well as high-frequency interference radiation.

Audio interfaces connected externally via USB 2.0 are more popular nowadays than PCI(e) cards. While the Firewire 400 interface was the external interface of choice until a few years ago, many manufacturers have moved on to USB2.0 interfaces once manufacturers overcame the initial problems with making high-performing and stable USB 2.0 interfaces. Additionally, Apple has nowadays replaced the Firewire 400/800 interface with the far more powerful Thunderbolt interface. This is not the complete end of Firewire, however, since Thunderbolt is downward-compatible to Firewire 800. All you need is the right adapter cable and you can still use Firewire. Interestingly, the Firewire 800 interface never really gained a large following in the world of audio. The only Firewire 800 interface that ever achieved market maturity is RME's Fireface 800. With all other Firewire manufacturers, Firewire still prevails. However, Firewire 400 and 800 are compatible if connected via adapter cable.

Firewire

Thunderbolt interfaces are becoming ever more popular on the market

Thunderbolt

Some pointers on the USB 3.0 interface:

USB

Many new computers come with high-performance USB 3.0 interfaces. While this is standard in the world of computers, the world of audio has not kept up: only few manufacturers offer audio interfaces with USB 3.0 ports, while USB 2.0 remains the standard. Though the makers of the USB 3.0 specification made provisions for downward compatibility to USB 2.0, this often causes trouble in practice. Apparently the stability and performance of your audio interface depends to a great degree on your USB controller and its driver. So pay special attention to the USB controller when you buy a new PC for your home recording studio. Some interface manufacturers, such as RME, provide information on their websites on tested computer systems with notes on chip set and USB controllers. Downward compatibility from USB 3.0 to USB 1.1 is no longer specified, by the way - so generally make sure that your (new) computer has one or two USB 2.0 ports to guarantee compatibility with USB 1.1 interfaces.

Power supply

Your computer's USB port can supply your interface with electric power through the USB connection in principle (bus power). However, the energy supplied is severely limited at 5 V / 500 mA. This is why only two- to four-channel interfaces with at most two mic amps are supplied in this manner. For interfaces with more than two pre-amps, direct connection to the mains is necessary. In comparison, Firwire can supply much more power at up to 33 V / 1.5 A. Nevertheless, manufacturers usually include a power supply pack with their larger interfaces. Some manufacturers offer both options for your convenience.

The limited power supply through the USB port presents another difficulty, namely with the headphones out. The available power is usually not sufficient to operate a headset at adequate volume. Sets with larger impedance are often relatively quiet as a result, while low-resistance headphones suffer noticeable distortion.

Pre-amps

If you want to create mic recordings in your home recording studio, you will require an interface with mic pre-amps. They should be low-noise, support a high amplification factor, and provide 48V supply power (phantom power). Unfortunately, many built-in pre-amps lack stamina where amplification is concerned. Some models only manage 48 dB gain, which is simply too little for many applications. Better models achieve at least 50 to 60 dB, a few even more. Concerning sound, however most of the pre-amps are good or even excellent, and their noise emission is sufficiently low for most professional uses.

Analogue and digital I/Os

When you decide to buy an audio interface, you'll also have to have a clear idea of how many inputs and outputs you require. For a small project studio used by an individual singer/songwriter, an interface with two mic channels is usually enough. If you want to record a complete drum set with the appropriate number of mics, however, you will need many more mic channels. Likewise, a large number of line ins may be necessary, for example if you plan to include a larger number of synthesizers simultaneously. Also, one or two high-impedance instrument ins should be featured. We should mention, though, that these Hi-Z ins are very susceptible to intereference by electric fields and often hum, so it is sometimes wiser to use a DI box and connect them to the interface via an available mic in.

RME Fireface UFX+ front

RME Fireface UFX+ reverse

On the output side, you'll need at least two mono outs (main out) in order to hook up a pair of monitor speakers. Many multi-channel interfaces, however, provide a much larger number of analogue outs. This is useful for example when you need to distribute signals to various musicians. In addition, a headphone connection is part of any interface's standard features. This output usually gives out the same signal as the main out, but you should make sure that the headphone channel has its own volume control.

Many interfaces come with digital audio paths in addition to the analogue outs. Usually, this will be a two-channel S/PDIF interface which is available either electrically via cinch or optically via TOSLINK. Many interfaces also provide an ADAT interface for multi-channel digital audio transmission. It can transmit a standard eight audio channels via optical cable. This interface is excellently suited to expanding the number of analogue channels with an AD/DA converter.

Direct monitoring

Let's return for a moment to our example of recording vocals to an already existing playback. The option to send the playback to the vocalist's headphones simultaneously with the vocals is essential. Now, we could of course send the mic signal which is being recorded in the software straight back to the headphones along with the playback. The problem, once more, is latency. Even when you use ASIO, the latencies are too great, since the signal first has to be converted and processed by the software before it can be sent back to the output.

So interface manufacturers have come up with something else, and their "magic" solution is direct monitoring. Direct monitoring can be effected either through the audio interface hardware or using software. In hardware direct monitoring, the analogue incoming signal is sent to the output before AD conversion and is thus added synchronously to the playback signal. There's therefore no danger of latency. This process works best with small interfaces with one or two channels only. It reaches its limits with larger interfaces, because with such interfaces it is most often desirable to send the different incoming signals to the output in a definable mixing ratio.

This is where software direct monitoring comes into its own. It involves a separate software mixer which is used to generate a mix for monitoring independently of the recording software. In doing so, the playback signal is added to the incoming signal without noticeable time delay. The necessary calculations are often done on a separate processor (DSP = Digital Signal Processing) in the interface, which means that the delay times stay extremely short.

Additional features

Many audio interfaces feature a MIDI interface for connecting a MIDI keyboard or other MIDI periphery devices in addition to the many audio interfaces.

Some manufacturers also use the DSP chip mainly installed for software monitoring to make effects such as EQ, dynamics, reverb or delay available for monitoring, too. This is very useful, if the vocalist wishes to have some reverb in their ears for a better performance, for example. Recording software would suffer from noticeable latency if you were to run this through it - but with the software DSP mixer, this is no problem.

Some manufacturers allow their interfaces to be cascaded through the data interface. This is a feature you can find mainly in PCI(e) audio cards and some Firewire interfaces. USB interfaces, on the other hand, hardly ever come with this feature.